Latest News

Remembering Sandra Joyce

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of Sandra Joyce. Sandy passed away on the morning of Thursday, February 14th at Toronto General Hospital with her family by her side. Sandy fought so hard. She was taken from us far too soon and will be missed.

This photo was taken by Sandy on one of her many quiet mornings on White Lake, where she would watch the sun rise from the dock, coffee in hand.

Kawartha now April, 2017

Troupe tells touching tale of family secrets

Lindsay Little Theatre takes a piece of history from a dark corner of Canada’s past and dramatizes its impact through the generations of one family in Homechild.

Troupe tells touching tale of family secrets

Catherine Whitnall

Pam Brohm, Marion Bays, John Cook and Arianna Koty (foreground) star in Lindsay Little Theatre’s upcoming production of Homechild, running April 21, 22, 28 and 29 at the troupe’s 55 George St. studio.

Kawartha Lakes This Week

By Catherine Whitnall

LINDSAY – Sometimes the past comes back to haunt us; sometimes it’s a good thing.

Such is the case with Lindsay Little Theatre’s presentation of

Homechild

by Governor General’s Award-winning playwright, Joan MacLeod, running April 21, 22, 28 and 29.

The play is grounded in the migration of more than 100,000 orphans and children who were given up for adoption who were sent from the United Kingdom to Canada between 1869 and 1948 to work as labourers or domestic help. It was believed the children would have a better chance for a healthy, moral life, but while some were welcomed into Canadian families, many were poorly treated and abused.

Champion of British Home Children to bring her story to Sarnia

Sandra Joyce, with personal connection to issue will speak at event Tuesday evening

By Editorial Staff April 10, 2017 Events, Local News

Photo credit of Sandra Joyce and Don Cherry by Paul Jackson

Sandra Joyce, a Toronto writer known for helping to facilitate an official apology for the actions of the British government in sending more than 100,000 children to Canada, is taking her story to Sarnia Tuesday evening, when she will speak to the monthly meeting of the Sarnia Historical Society at the Sarnia Library Theatre. The free presentation begins at 7:30 p.m.

Joyce, a published author, has become a well-known advocate on the issue since she realized her own family connection in 2004.

The British Home Children scheme, which was initially motivated by social and economic forces, saw churches and philanthropic organizations sending orphaned, abandoned and pauper children to Canada and other Commonwealth countries between 1869 and 1932.

While many believed that the children would have a better chance for a healthy, moral life in rural Canada, families here often welcomed them as a source of cheap farm labour and domestic help.

Unfortunately, as Joyce found when she discovered her own father and uncle were sent to Canada from Scotland in 1925, the scheme often resulted in families being separated.

“My father was just 15 when he arrived in Canada,” said Joyce. “I thought he was an adult but being so wrong explains why he was a quiet, reserved man who had difficulty with emotional connections.”

The program also resulted in children facing malnourishment.

Since bringing the issue to the forefront through her book, “The Street Arab,” Joyce has spoken with numerous descendants of the British Home Children era.

She her self was instrumental in securing an official apology to British Home Children in the House of Commons, which was issued on February 16, 2017.

Joyce said she regrets that her father didn’t have the opportunity to tell his story. She hopes to pass on what her father “was too ashamed” to reveal about his experience.

“When you look at a group that large, it has an effect on the development of a country,” she said. “It would have helped as a family to be able to talk about it. It’s a Canadian story that should be taught. We all need to know about our heritage and it doesn’t matter if you’re directly connected or not.”

Joyce found about her father’s experience by typing in his name into a database at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Halifax, N.S. That was in 2004, two years after her father had died.

More information on the issue is available at http://britishhomechild.com/.

Toronto writer instrumental in recent House of Commons apology to British home children

Toronto writer instrumental in recent House of Commons apology to British home children

By Barbara Simpson, Sarnia Observer

British home children advocate Sandra Joyce is pictured here after the House of Commons issued a formal apology to these children who worked in Canada as indentured farm workers and domestics. Pictured here, from left to right, are NDP MP Jenny Kwan, Green Party leader Elizabeth May, Bloc Quebecois MP Luc Theriault, Joyce, Liberal MP Judy Sgro and Karen Mahoney, president of British Home Children Group International.

Sandra Joyce had to uncover a secret her father held for close to 80 years in order to find the family she had always wanted.

The Toronto-based writer – who was raised by two British ex-pats – grew up without any contact with her father’s family. She was told she had an uncle, but that was it.

Ultimately it would take a visit to the Canadian Museum of Immigration after her father’s death and hours of research to find the full story: her father had been a British home child, plucked from his family in 1925 to come to Canada to work in the fields of Ontario.

“My dad never spoke of this,” Joyce said. “When I got all of these documents, it was one surprise after another. The biggest surprise, of all, was he had a sister who remained in Scotland and he never spoke about, so we’ve managed to trace their family.”

Joyce has since met her paternal first cousins. She even stayed in the Tower of London with a first cousin who is the tower’s only female Beefeater.

“If I had never found out about my father being a British home child, I would never been able connect with his family,” Joyce said, noting the process of reunification has been “almost overwhelming.”

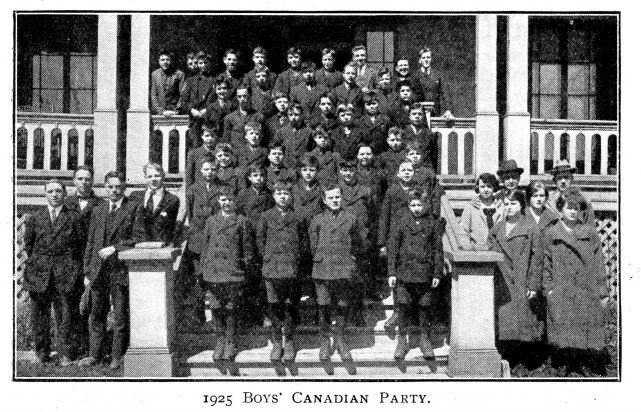

Robert Joyce, 15, and his brother Thomas, 12, are pictured here in this photo taken when they arrived at a receiving home for British children in Brockville, Ont in 1925. More than 100,000 British children — including Robert and Thomas — went sent to Canada to work as indentured farm workers and domestics from 1869 into the 1930s. (Handout)

Joyce is now on a mission to help other descendents of British home children find their lost families scattered across the world.

For more than a decade, Joyce has travelled across Canada to share the stories of these often-forgotten child labourers and provide support to their families searching for lost loved ones. She has also published a series of novels based on the experiences of British home children.

Joyce recently helped secure a formal apology to British home children from the House of Commons.

Joyce will share her family’s story, as well as her years of research on British home children, at the Sarnia library theatre April 11. Joyce last visited Sarnia in 2012 – a community where she says “quite a few” British home children were sent to work.

More than 100,000 children are believed to have been sent from Britain to Canada to work as indentured farm workers and domestics from 1869 into the 1930s.

These children – either orphaned, abandoned or poor – were sent to Canada by British churches and philanthropic organizations. Some children were as young as four, and often times, siblings would be separated from each other.

In 1925, Joyce’s father Robert was sent to Canada at the age of 15 along with his 12-year-old brother Thomas. They were sent to different farms in Ontario, and despite efforts to connect through their receiving home in Brockville, they never reconnected.

“My uncle wrote (the home) and asked for his brother’s address. Well, they didn’t know the address at the time,” Joyce said. “Then my father wrote to Brockville looking for his brother’s address, which they didn’t know at the time.”

Along with separation anxiety, Joyce said some British home children also had to grapple with abuse and neglect because once children were sent to Canada, it was the “luck of the draw” as to the conditions they would live in.

Joyce’s father Robert was ultimately released from the program at the age of 18. He moved to Toronto and eventually became a supervisor at Seaton House, the largest men’s homeless shelter in Toronto.

Robert went on to marry a fellow British ex-pat and then started a family of his own.

He died at the age of 93 in 2002.

Two years later, Joyce found his name on a passenger list at the Canadian Museum of Immigration in Halifax. Robert was part of a group of children who emigrated to Canada at the time – a fact that left Joyce searching for answers.

“At the time, I said, ‘Why don’t I know about this story? It would have made such a big difference in our lives as a family if we had known this,’” she said.

“He felt, I guess, ashamed that he was part of this group that was stigmatized in Canada.”

During that era, Joyce said society was wrapped up in a discussion about eugenics because people at the time thought poor children were the offspring of degenerates.

Looking back, Joyce said she can see how that – along with the fact her father came to Canada with few possessions – formed his lifelong need to always be financially secure as an adult.

While her father never told his own story, Joyce said she likes to think that in light of today’s more accepting society that “maybe he would have changed his mind and want it to be told.”

Joyce said the plight of British home children is a story shared by all Canadians.

“It’s one that affects so many people – so many Canadians – but it’s also a huge part of our history,” Joyce said. “Maybe it wasn’t the best part of our history, but it’s still part of our history, and we as Canadians don’t know enough about our history.”